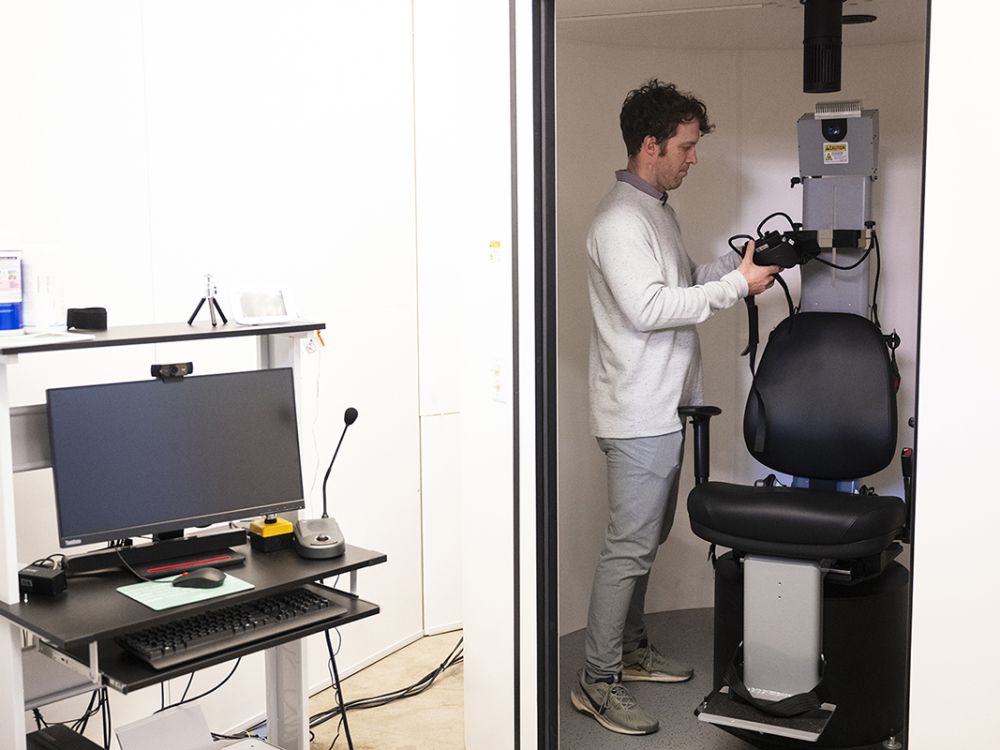

MISSOULA – Please don’t call it a spin-and-puke chair, even if the special equipment in Brian Loyd’s 91次元 lab is designed to induce motion sickness. He prefers “yaw-plane rotary chair.”

In 2024, Loyd and fellow UM scientist Andy Kittelson landed a three-year, $4.8 million grant from the U.S. Office of Naval Research. Their goal: develop new ways to help Navy pilots combat motion sickness. They also earned another $1.5 million Department of Defense grant to help military personnel with traumatic brain injuries regain their balance.

Their work may assist people far beyond the military, including older adults struggling with dizziness, inner ear dysfunction, balance and gaze control.

“We are recruiting people who get motion sickness and seeing if we can reduce it,” Loyd said. “The work is important for a lot of reasons, but, of course, we’d love to help give our pilots an advantage.”

Their motion-sickness studies are just one part of UM’s robust research enterprise, which in fiscal year 2025 posted yet another record for expenditures at $149.9 million. The high mark from the previous year was $143.8 million.

Scott Whittenburg, UM vice president for research and creative scholarship, said the new record reflects broader participation across campus from units seeking federal grants.

“We’re seeing more involvement from units that historically have not pursued external funding,” said Whittenburg, who has overseen 12 years of continual research growth at UM. “While our overall increase this year is modest, the growth is coming from more places across campus, and that’s encouraging.”

He said Zach Rossmiller, UM’s chief information officer, offers an example of a unit that doesn’t historically chase federal grants and contracts. Rossmiller leads UM Information Technology, and he helped land $3.4 million in grants to help boost the University’s IT research infrastructure.

But has UM reached the zenith of its research growth? Whittenburg said expenditures represent a “lagging indicator,” reflecting spending from multiyear grants awarded in prior cycles. In FY25, federal agencies tightened the purse strings and issued significantly fewer requests for proposals. This is an issue for universities nationwide.

Whittenburg said UM submitted 720 grant or contract proposals in 2024, and that number dropped to 564 last year. This will likely result in fewer awards in the coming year.

“There is uncertainty about what the trajectory will look like,” he said. “Because our awards typically span three to five years, the impact of fewer proposals is smoothed. But at some point, fewer proposals will mean fewer awards and, eventually, lower research expenditures.”

Whittenburg said budget signals from Washington, D.C., remain mixed. While cuts have been recommended to major funding agencies like the National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health, Congress has advanced plans to increase science funding – a development Whittenburg views as stabilizing.

“I know right now our research is running about 3% ahead of last year, which is pretty good,” he said. “We’ll need to see how the coming months go to see if we can continue growing.”

He said the Montana Climate Office at UM, led by Kelsey Jencso, could become a future driver of research momentum. That office recently secured an NSF-funded Regional Research Innovation Incubator planning grant focused on drought and hazard resilience. This new seed project could grow into a major multiyear federal investment for Montana and the region. It builds upon a previous $21 million grant in 2020, which built the Montana Mesonet weather monitoring network.

Another research effort showing promise is RESOLVE, a rural health collaboration between UM and St. Patrick Hospital in Missoula. Whittenburg said the new program will design and deliver research-driven strategies and health care models to improve access and outcomes for rural and Indigenous populations.

“The current administration is outlining the kinds of research it wants to fund,” he said. “We need to decide how our projects can fit into that. How do we encourage, perhaps, the kinds of research that will be included into those federal priorities? Those right now seem much more about national security and infrastructure. UM is strong in natural resources, forestry, drought, flood and disaster resilience. We need to help the federal government see these as investment priorities for the country.”

Whittenburg was instrumental in helping UM earn “R1” status as a top-tier research and doctorate-granting institution in 2022, and that designation was renewed in 2025. Only about 3.7% of degree-granting U.S. colleges achieve R1 status. He said UM is maturing as a research university.

“There is a trajectory,” he said. “At first it’s lone faculty members working with themselves on campus. And as you mature, you start collaborating and working as a sub-award with those at larger research institutions. And then you reach a point where you are sub-awarding to other universities, and that’s where we’re at currently.”

As for UM’s motion-sickness researchers, they are in the process of constructing an upgraded spin chair. It will have the capacity to move subjects up and down, side to side and back and forth in multiple directions. Its movements will be so robust that it is being built on a massive slab of concrete that once supported a UM newspaper printing press.

“We have barf bags handy, but we hope it never gets to that,” Loyd said with a laugh. “We are going to learn a lot.”

###

Contact: Dave Kuntz, UM director of strategic communications, 406-243-5659, dave.kuntz@umontana.edu; Scott Whittenburg, UM vice president for research and creative scholarship, 406-243-6670, scott.whittenburg@umontana.edu.