By Libby Riddle, UM News Service

MISSOULA – On a hillside in northwest Montana, Mahdieh Tourani secures a camera to a tree. She gives the straps anchoring the camera a good tug, and when it doesn’t move, she steps back to admire her handiwork. Sensing her movement, the camera snaps a photo. She kneels back in front of it and checks the picture. Her frame is in focus, and there are no branches blocking the camera’s view. It’s good to go.

Tourani uses cameras like these to study animals where they are often hard to find – from densely forested northwest Montana to the Himalayas. Her work has advanced how scientists – including students at the 91次元 – use this technology to answer important questions about wildlife.

As a UM assistant professor of quantitative ecology with the W.A. Franke College of Forestry and Conservation, Tourani studies some of the most important questions in wildlife ecology: How many animals are there and where are they spending their time? How do they interact with humans and one another? These fundamental questions inform how people make decisions for wildlife populations and conservation. Using technology like trail cameras, Tourani ensures that the answers to those questions are reliable.

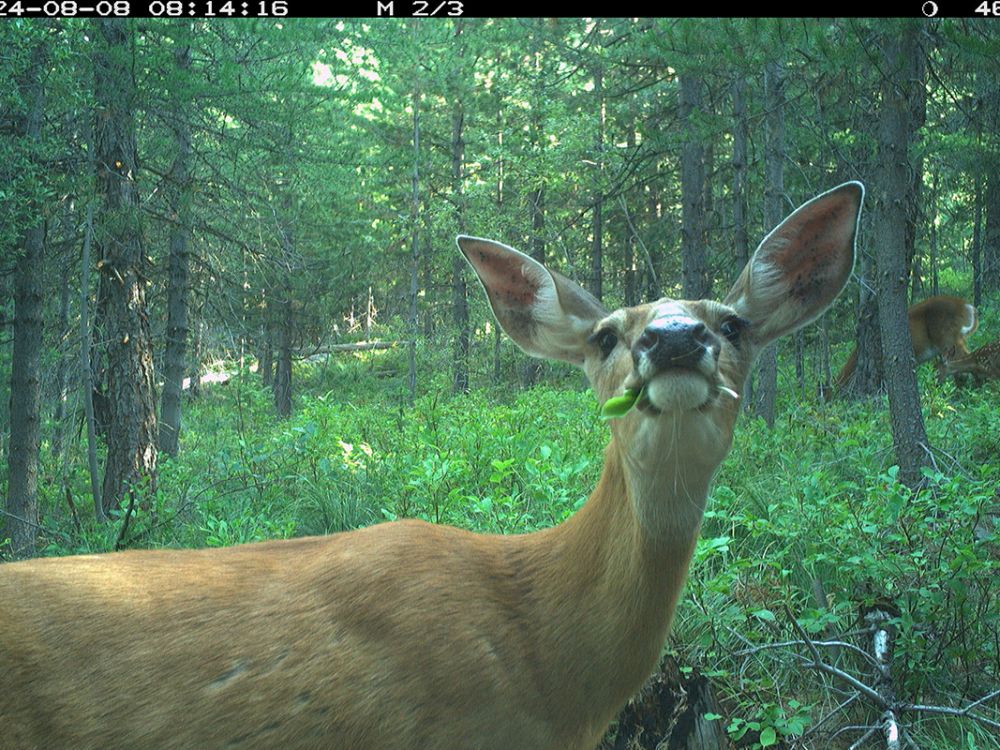

These cameras use a combination of motion and heat-sensing technology to snap a picture when an animal passes. They’re often called “camera traps” because they are a useful alternative to physically capturing animals, which can be dangerous for both animals and scientists. Other advantages include a lower cost compared to other types of survey methods, and scientists no longer have to sit in the field for hours or days waiting to see animals that may not be present.

“And the coolest thing about them is that there is a huge community that uses camera traps around the world,” Tourani said. “This brings lots of opportunities for collaboration.”

That spirit of collaboration extends to UM’s own campus, where students in the Wilderness and Civilization program use camera traps to study Missoula’s wildlife. Students in this semester-long program have installed cameras at the

same spots along Rattlesnake Creek at the same time for the past five years. The students’ cameras have caught over 25 different species, including black bears exploring Missoula’s Greenough Park and mountain lions traveling through the nearby Rattlesnake National Recreation Area.

“Last fall we caught a beaver, and then an hour later, that beaver was swinging from a bear’s mouth,” said program director Andrea Stephens. “The group went absolutely bonkers over that.”

After only a few weeks of capturing photos, each of the students’ cameras contains over 5,000 images. For a long time, the sheer volume of data was one of the biggest challenges to using camera traps for research. Luckily for students and scientists alike, Tourani helped develop a new tool for analyzing camera trap footage called Wildlife Insights. This software program can take thousands of images, identify the species present and generate maps of where species are and what they’re doing.

The Wilderness and Civilization students use this tool and their cumulative years of data to answer questions about patterns in Missoula’s wildlife activity. In the past they’ve investigated changes in the number of particular species over time, the presence of different species along the creek corridor and times of high and low wildlife activity. This year’s cohort is exploring the distribution of different species along a spectrum of urban development to wildland.

“It’s important to me that students recognize all the wildness we’re coexisting with every day,” Stephens said. “And these cameras allow us to do that.”

Camera trap surveys have become one of the most important tools for monitoring wildlife populations, Tourani said. Learning to operate camera traps and design research studies with them is a valuable skill for students heading into wildlife careers. Having the additional experience working with Wildlife Insights makes these students more marketable and introduces them to collaboration opportunities with scientists and wildlife managers around the globe.

“Learning the skillset required for a camera trap survey goes a long way in the wildlife profession,” Tourani said.

###

Contact: Dave Kuntz, UM director of strategic communications, 406-243-5659, dave.kuntz@umontana.edu; Libby Riddle, science communications coordinator, W.A. Franke College of Forestry and Conservation, elizabeth.riddle@umontana.edu.